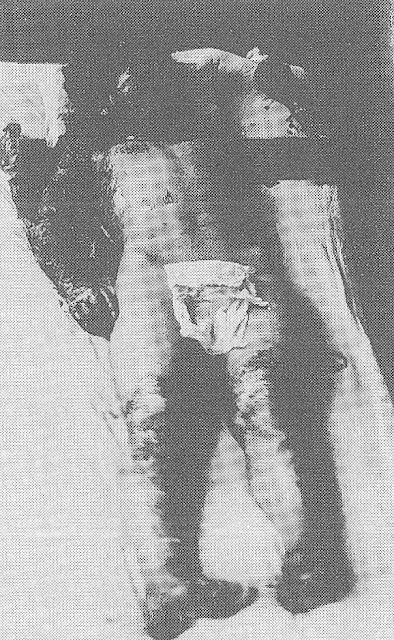

The keloid formation occurred on burned skin. Keloids that formed and swelled from the chest to the breasts of female atomic bomb survivors exposed to the Nagasaki atomic bomb were photographed in February 1947.

The sequelae and genetic effects of the atomic bombs included the following atomic bomb diseases

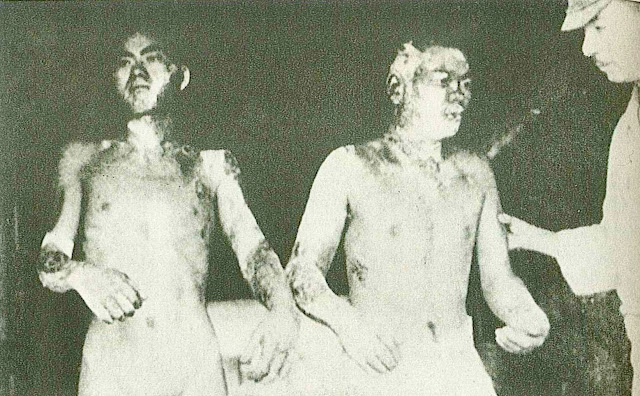

1) Keloids: In the center of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, near the hypocenter, victims who received significant primary burns or flame burns were injured simultaneously by the tremendous blast and radiation, and most of them died immediately or within the same day. They were at least near the end of Stage I. These secondary burns were similar in nature to those of flash fires, resembling grade 3 and grade 4 burns that cause significant damage to the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. These lesions were often associated with flash burns and took a long time to heal. The poor living conditions just before and after the end of the Pacific War also contributed to this long healing period. Burns festered, leading to delayed wound repair and the formation of thick scars in the subcutaneous tissue. The scar tissue shrank, resulting in deformity and functional impairment. These sequelae were more pronounced on the face, neck, and fingers.

The majority of flash burns (primary burns), which occurred frequently in areas within about 2,000 to 3,000 meters of the hypocenter, initially healed in a relatively short time and resulted in the formation of simple, thin scars. This is a difference between the two groups. Bone maturation was studied in 1973 and included 556 children exposed in utero in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and a control group. It was found that epiphyseal closure of the hands progressed about 6 to 7 months later in boys and about 8 to 9 months later in girls than previously reported in healthy children.

2) Adult life of in utero survivors: In 1973, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission reported on the late effects of in utero exposure. The A-bomb diseases observed in persons exposed to high doses of radiation in utero were: (1) retardation of growth and development (height, head circumference) and increased incidence of microcephaly; (2) increased mortality, especially in infants; (3) temporary decrease in antibody production; and (4) increased frequency of chromosome aberrations in peripheral lymphocytes. However, there was no increase in the incidence of leukemia or cancer, nor was there any change in fertility or in the sex ratio of children born to exposed women.

3) Microcephaly As for the frequency of microcephaly, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission found 33 cases of microcephaly among 169 prenatally exposed survivors in Hiroshima. These 33 cases included 15 cases of mental retardation, 18 cases of normal mental development, and 13 cases of head circumference more than 3 standard deviations smaller than the standard deviation. Among 183 children exposed in utero in Hiroshima, we found 33 cases of microcephaly; 14 of the 33 cases had a marked degree of microcephaly. With regard to children exposed in utero in Nagasaki, the authors noted that the average head circumference of high-dose survivors (within 1.5 km and more than 50 rads) was low. They reported microcephaly in 7 of 102 children exposed in utero within 2 km of the hypocenter in Nagasaki and in 5 of 173 children exposed 2 to 3 km from the hypocenter.